Anne Maria Clarke @ the V&A

There is a golden thread that reaches back beyond the classical world from the paintings of Botticelli during the magnificent flowering of the renaissance through to the art of present day. It seems that for hundreds of years in between it’s trail has been lost, forgotten, hidden or simply disregarded – then for no apparent reason it has re-emerged into popular consciousness, re-discovered, re-imagined by new artists who have enchanted us anew. So what is the nature of this seemingly eternal quest? What do we seek, that slips so easily from our grasp?

*****

When I saw the V&A were putting on this exhibition I knew straightaway I had to come. Featuring over 50 original works by Botticelli it looks at how his work has influenced subsequent generations of artists like William Morris and the pre-Raphaelites' through to Andy Warhol, Elisa Schiaparelli and countless others. The story however begins a long time before even Botticelli was born, many hundreds of years ago in the classical world of Ancient Rome and Greece, when the mythological figures which were to feature so prominently in the early Renaissance, were actual gods and goddesses and where the humanist values that so influenced the renaissance, were thought to have been first conceived.

*****

When I saw the V&A were putting on this exhibition I knew straightaway I had to come. Featuring over 50 original works by Botticelli it looks at how his work has influenced subsequent generations of artists like William Morris and the pre-Raphaelites' through to Andy Warhol, Elisa Schiaparelli and countless others. The story however begins a long time before even Botticelli was born, many hundreds of years ago in the classical world of Ancient Rome and Greece, when the mythological figures which were to feature so prominently in the early Renaissance, were actual gods and goddesses and where the humanist values that so influenced the renaissance, were thought to have been first conceived.

Birth of Aphrodite

Fresco created for Alexander the Great by Apelles; ancient Greece’s most celebrated painter.

It was into this largely forgotten world that poets of the day like Poliziano and humanist philosophers such as Marsilio Ficino delved and took their inspiration. What they discovered was that the ideals which had flourished in Ancient Greece were themselves derived from the even older eras of Ancient Egypt, pre-history and what has sometimes been called deep time.

These ideals had been quietly preserved throughout the middle ages but it was not until after the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453 - when many Greek scholars fled to Italy, bringing with them important philosophical works such as Plato’s Symposium and the older Corpus Hermeticum and Aasclipius – that they became available to Florentine scholars.

Under the patronage of the powerful Medici family, Marsilio Ficino translated these manuscripts and later established the Florentine Academy, based upon Plato’s ancient Greek Academy - and here the ideas, now known as Neo – Platonism were revived – and it was these ideas – very different from those of the dominant paradigm of the day – that underpinned and informed the artistic expression of renaissance art in all its forms.

These ideals had been quietly preserved throughout the middle ages but it was not until after the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453 - when many Greek scholars fled to Italy, bringing with them important philosophical works such as Plato’s Symposium and the older Corpus Hermeticum and Aasclipius – that they became available to Florentine scholars.

Under the patronage of the powerful Medici family, Marsilio Ficino translated these manuscripts and later established the Florentine Academy, based upon Plato’s ancient Greek Academy - and here the ideas, now known as Neo – Platonism were revived – and it was these ideas – very different from those of the dominant paradigm of the day – that underpinned and informed the artistic expression of renaissance art in all its forms.

The Birth of Venus – Goddess of Love & Beauty

Sandro Botticelli 1482 -85

It is said that the naked Venus, emerging from the sea was the first rendering of a naked woman to be seen in Italy since the fall of the Roman Empire. And what a symbol of the renaissance she was, re- born from the deep amidst a shower of rose petals – the lost goddess of love, hidden within the collective unconscious for hundreds of years – an archetype of the Divine Feminine, rendered by Botticelli in all her womanly sensuality – a seeming far cry in every conceivable way from the depictions of the chaste and demurely robed Madonna that had populated the Medieval world. Or was she?

In stark contrast to the harsh Christian dogma of original sin, the ancient Greeks and their philosophical predecessors had believed there to be a divine spark of love within each individual. Nakedness had been celebrated in both gods and mortals alike and the contemplation of physical beauty was believed – in accordance with Plato’s theory of forms – to be able to facilitate rather than inhibit the experience of the sublime. The nakedness of Botticelli’s Venus therefore - seen through this platonic lens of love...is altogether different from that of the shamed Eve, expelled from Paradise or the Virgin mother, innocent of all perceived taint of the flesh.

Botticelli however, together with his teachers and patrons sought not only to introduce these new ideals but to gently harmonize and reconcile them with Christianity.

Brunellesco the Florentine architect/engineer responsible for the erection of the famous Cathedral Dome had around 1415 discovered the system for linear perspective which had radically altered the way in which paintings were created. The illusion of depth, unknown in Europe until this time was becoming increasingly popular along with other new techniques that allowed the creation of more sophisticated, life like figures and scenes, yet Botticelli consciously retained both the flat, medieval mode of presentation and a simplicity of form and posture associated with familiar depictions of the Madonna.

The way Venus’s head is tilted, her tender, reflective and introspective expression through to the modesty revealed in her gesture – it is as if – even in her nakedness and obvious sensuality, she retains her innocence and her divinity in a way that could very well be compatible with that of the Virgin Mary - and maybe there was even the intention to hint at their ultimate indivisibility.

In stark contrast to the harsh Christian dogma of original sin, the ancient Greeks and their philosophical predecessors had believed there to be a divine spark of love within each individual. Nakedness had been celebrated in both gods and mortals alike and the contemplation of physical beauty was believed – in accordance with Plato’s theory of forms – to be able to facilitate rather than inhibit the experience of the sublime. The nakedness of Botticelli’s Venus therefore - seen through this platonic lens of love...is altogether different from that of the shamed Eve, expelled from Paradise or the Virgin mother, innocent of all perceived taint of the flesh.

Botticelli however, together with his teachers and patrons sought not only to introduce these new ideals but to gently harmonize and reconcile them with Christianity.

Brunellesco the Florentine architect/engineer responsible for the erection of the famous Cathedral Dome had around 1415 discovered the system for linear perspective which had radically altered the way in which paintings were created. The illusion of depth, unknown in Europe until this time was becoming increasingly popular along with other new techniques that allowed the creation of more sophisticated, life like figures and scenes, yet Botticelli consciously retained both the flat, medieval mode of presentation and a simplicity of form and posture associated with familiar depictions of the Madonna.

The way Venus’s head is tilted, her tender, reflective and introspective expression through to the modesty revealed in her gesture – it is as if – even in her nakedness and obvious sensuality, she retains her innocence and her divinity in a way that could very well be compatible with that of the Virgin Mary - and maybe there was even the intention to hint at their ultimate indivisibility.

La Primavera - Botticelli 1492

Venus stands at the center of her orange grove as if announcing the arrival of Spring. She is surrounded by nine mythological figures from the classical world, Zephyrus, god of the wind, Hamadryad, Chloris, the three dancing graces, goddesses of joy, charm and beauty, then Mercury and Venus’s cherub son Cupid, poised to fire his arrow of love.

With these re- animated gods and goddesses came the stories associated with them and the immense psychological insight into the mysteries of the human psyche that had been hidden alongside them.

The two paintings, taken together are said to represent the two stages or incarnations of the goddess.

’Here again we come upon the twin Venuses: one clearly the ability of the soul to know divinity; the other, the ability of the soul to propagate lower forms.’

Therefore let there be two Venuses in the soul, the one heavenly, the other earthly. Let them both have a love, the heavenly for the reflection upon divine beauty, the earthly for generating divine beauty in the earthly.”

From Ficino’s Commentary on Plato’s Symposium

With these re- animated gods and goddesses came the stories associated with them and the immense psychological insight into the mysteries of the human psyche that had been hidden alongside them.

The two paintings, taken together are said to represent the two stages or incarnations of the goddess.

’Here again we come upon the twin Venuses: one clearly the ability of the soul to know divinity; the other, the ability of the soul to propagate lower forms.’

Therefore let there be two Venuses in the soul, the one heavenly, the other earthly. Let them both have a love, the heavenly for the reflection upon divine beauty, the earthly for generating divine beauty in the earthly.”

From Ficino’s Commentary on Plato’s Symposium

Botticelli's Fall from Grace

In 1494 Florence unexpectedly became a dictatorship in which paintings like the Birth of Venus and La Primavera were reviled. It seemed for a while that no reconciliation between the gods and goddesses of the past and those of the present could be tolerated. The dictatorship did not last long and certainly did not hold back the inevitable tide of the Renaissance but while it did hold sway in the city Botticelli was forced to take vows of renunciation after which he returned to painting religious themes and died in obscurity a few years later.

Those brief years of the early renaissance, when Botticelli was at his peak were precious indeed, for in both the Birth of Venus and La Primavera we see a very pure rendering of the high ideals that inspired the Florentine school and – in spite of their innocent simplicity or more likely because of it – they have achieved iconic status as two of the most well known and well loved paintings in the world.

It’s difficult to imagine knowing what we do now, that just 10 years after they were created – they fell so thoroughly from grace - and that Botticelli was forgotten for nearly three centuries - but as Carl Jung reminds us, nothing of the psyche is ever lost – we may loose contact with its content, it may fall from our grasp into the vastness of our collective unconscious, emerging for a time only in dreams that desert us the moment we open our eyes. Yet sooner or later it will return, re-kindled by a new generation - as it did again in the mid-nineteenth century.

Those brief years of the early renaissance, when Botticelli was at his peak were precious indeed, for in both the Birth of Venus and La Primavera we see a very pure rendering of the high ideals that inspired the Florentine school and – in spite of their innocent simplicity or more likely because of it – they have achieved iconic status as two of the most well known and well loved paintings in the world.

It’s difficult to imagine knowing what we do now, that just 10 years after they were created – they fell so thoroughly from grace - and that Botticelli was forgotten for nearly three centuries - but as Carl Jung reminds us, nothing of the psyche is ever lost – we may loose contact with its content, it may fall from our grasp into the vastness of our collective unconscious, emerging for a time only in dreams that desert us the moment we open our eyes. Yet sooner or later it will return, re-kindled by a new generation - as it did again in the mid-nineteenth century.

The Pre –Raphaelites – return to innocence

Between the mid 1800’s and early 1900’s,when the planet Neptune was discovered (1846) and Freud, Jung and their followers began their work on exploring the unconscious and apportioning huge importance to dreams, a group of London artists mounted a challenge to the dominant mode of expression in art.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was originally composed of John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabrielle Rossetti and their expressed intent was to return to a style of art that re-dated Raphael. They felt the production of art had become overly mechanistic and they rejected the principals of the Mannerist style that had dominanted after Raphael. For the first few years they were openly ridiculed in the press for their break away realism and lack of prescripted form – until the respected and trusted art critic John Ruskin, who had been observing their progress from afar, publically endorsed them in an article he wrote for the Times newspaper. From then on the P.R.B. could do no wrong and soon enthralled the general public.

They were later joined by other artists and two distinct streams developed – one focused on realism, the other, of more interest to us here was led by Rossetti with William Morris and Edward Burne–Jones, all unabashed Romantics with interests in Medieval romance, spirituality, mysticism and even altered states of consciousness and who greatly admired the writings of Homer, Dante Alighieri and poets like Keats, Shelley and Tennyson.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was originally composed of John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabrielle Rossetti and their expressed intent was to return to a style of art that re-dated Raphael. They felt the production of art had become overly mechanistic and they rejected the principals of the Mannerist style that had dominanted after Raphael. For the first few years they were openly ridiculed in the press for their break away realism and lack of prescripted form – until the respected and trusted art critic John Ruskin, who had been observing their progress from afar, publically endorsed them in an article he wrote for the Times newspaper. From then on the P.R.B. could do no wrong and soon enthralled the general public.

They were later joined by other artists and two distinct streams developed – one focused on realism, the other, of more interest to us here was led by Rossetti with William Morris and Edward Burne–Jones, all unabashed Romantics with interests in Medieval romance, spirituality, mysticism and even altered states of consciousness and who greatly admired the writings of Homer, Dante Alighieri and poets like Keats, Shelley and Tennyson.

The Renaissance of Venus

1877 Walter Crain

1877 Walter Crain

This second wave of Pre-Raphaelite artists, once described as a 'quasi – classical semi-mystical school’ included Walter Crane, whose Renaissance of Venus is in the current exhibition. They were collectively referred to as the neo-Italians – as their work was derivitive of the Florentine Quattro centro period. Critics berated them for escaping into a kind of dreamworld that did not address the issues of the day yet others like Ruskin seemed to understand that behind the mythic, enchanted images that populated their work, there was a huge consciousness and sensitivity to the suffering in the world about them.

William Morris was a professed socialist and had created Morris & Co, a company creating hand-crafted fabrics and furniture that were sold for what he called a ‘just price’, reflecting his dismay at the increasing mechanisation and mass production of goods he observed around him.

In Oxford he and Burne – Jones are said to have read aloud the Legends of the Holy Grail and saw in the depictions of The Wasteland, the terrible polluted squalor of the industrial cities that surrounded them. Burne – Jones, who had grown up in Birmingham, amidst the some of the ugliest industrial landscapes in Britain is said to have despaired at the relentless march of science without regard to the quality of life.

“The more materialistic science becomes" he wrote somewhat defiantly, “the more angels I shall paint.”

The movement has often been referred to as the cult or religion of Beauty and certainly .... in its uninhibited celebration the feminine principle, it clearly took up the thread of Botticelli and the ideals of neo-Platonism that had unravelled centuries earlier and fallen into the realms of the unconscious.

Edward Burne-Jones’s depiction of the Sleeping Beauty is a perfect image and metaphor of lost beauty, sleeping behind a hedge a thorn for one hundred years – and the young pre-Raphaelites' – to continue the metaphor – can very well been seen as the chivalrous knights who discover and rescue her from her bower, breaking the sleep-spell with a tender kiss and in so doing usher in a new Victorian style renaissance in which the archetype of beauty, once goddess in the form of Venus and the Greek Aphrodite – is re-awakened like the Sleeping princess in the fairy tale.

William Morris was a professed socialist and had created Morris & Co, a company creating hand-crafted fabrics and furniture that were sold for what he called a ‘just price’, reflecting his dismay at the increasing mechanisation and mass production of goods he observed around him.

In Oxford he and Burne – Jones are said to have read aloud the Legends of the Holy Grail and saw in the depictions of The Wasteland, the terrible polluted squalor of the industrial cities that surrounded them. Burne – Jones, who had grown up in Birmingham, amidst the some of the ugliest industrial landscapes in Britain is said to have despaired at the relentless march of science without regard to the quality of life.

“The more materialistic science becomes" he wrote somewhat defiantly, “the more angels I shall paint.”

The movement has often been referred to as the cult or religion of Beauty and certainly .... in its uninhibited celebration the feminine principle, it clearly took up the thread of Botticelli and the ideals of neo-Platonism that had unravelled centuries earlier and fallen into the realms of the unconscious.

Edward Burne-Jones’s depiction of the Sleeping Beauty is a perfect image and metaphor of lost beauty, sleeping behind a hedge a thorn for one hundred years – and the young pre-Raphaelites' – to continue the metaphor – can very well been seen as the chivalrous knights who discover and rescue her from her bower, breaking the sleep-spell with a tender kiss and in so doing usher in a new Victorian style renaissance in which the archetype of beauty, once goddess in the form of Venus and the Greek Aphrodite – is re-awakened like the Sleeping princess in the fairy tale.

The Rose Bower

Edward Burne-Jones 1885/1890

The Fall of the Pre-Raphaelites

Eventually the popularity of these Victorian dreamers waned and like Botticelli before them, their work fell from grace, particularly after the first world war when it became seen as very unfashionable. Like old upright pianos that had once stood at the heart of the home, hundreds of pre- Raphaelite works were discarded, thrown out or sold off for practically nothing.

Botticelli's Venus in the Modern Era

It was not until the 1960’s that they made a come back – with many of the now iconic images like Rossetti’s Proserpine, being made into posters by Athena, the famous poster company – to adorn the walls of student bedsits and teenage bedrooms along side those of political activists like Che Guevara. It was yet another time of magnificent dreams – the Californian 'summer of love and peace', the stuffing of flowers down the shafts of American soldiers rifles, of the Beatles All you need is love.

Two decades later in 1984 Andy Warhol created his garish version of the Botticelli Venus, Dolce & Gabbana showed a dress featuring the image on their Milan catwalk in 1993 - a dress recently worn by Lady Gaga when she performed her hit song Venus, in 2015 - completing the Botticelli beauties absorption into Pop Art and Culture. The French Artist Alain Jacquet has also represented her as a petrol pump – revealing and perhaps warning like Wahol and William Morris before, of the dangers inherent in the commoditization and objectification of the feminine without reference to the soul.

Two decades later in 1984 Andy Warhol created his garish version of the Botticelli Venus, Dolce & Gabbana showed a dress featuring the image on their Milan catwalk in 1993 - a dress recently worn by Lady Gaga when she performed her hit song Venus, in 2015 - completing the Botticelli beauties absorption into Pop Art and Culture. The French Artist Alain Jacquet has also represented her as a petrol pump – revealing and perhaps warning like Wahol and William Morris before, of the dangers inherent in the commoditization and objectification of the feminine without reference to the soul.

Venus

Andy Warhol 1984

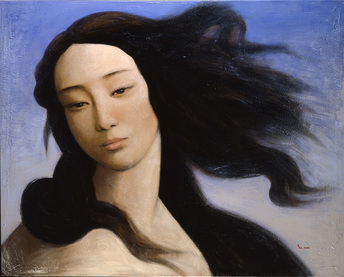

There is one modern painting in the exhibition though, that for me at least really does evoke Botticelli's renaissance Venus in a way which is surprisingly arresting and this is the 2008 piece by Yin Xin. Unlike the acid prints of Warhol where Venus looks like she has just been given an electric shock - Yin Xin's tranquil,dark haired goddess,with its delightful Asian twist seems to be an inversion of the modern, sometimes semi-pornographic renderings. Yin Xin brings us full circle with his powerful, mysterious and introspective beauty so deeply resonant of the Platonic yearning for the sacred - and it brings to mind for me too - Marina Warner's enlightening explanation of the term Virgin goddess - meaning - not as is commonly supposed - the condition of a woman who has had not intercourse with a man - but rather - the condition of a woman who is whole and complete within herself.

Venus - after Botticelli

Yin Xin 2008

The golden thread we spoke of at the start is itself an image from Greek mythology. It belonged to Ariadne. Those who discover it and trace it’s path are led through the illusions of the labyrinth, on an initiatory journey during which they will be severely tested before eventually confronting and overcoming the fearsome Minotaur who guards the treasures at the heart of the quest.

The myths, legends and archetypes; the artists and their wondrous creations - are the treasures, each reflecting as aspect of the mystery, that maybe strung upon Ariadne's golden thread like translucent pearls upon a priceless necklace.

It seems that those artists, thinkers and even their patrons like the Medici, throughout the many centuries of this story – have somehow resonated with this quest. They have championed the theme of divine love and beauty and have attempted in their various ways to express – to re -imagine for us – what this illusive mystery may be or may not be.

The high renaissance artist Raphael once said of the archetype of the goddess, Venus and the Madonna alike...and this seems like as good as any place to end...

“She is divine serenity made human flesh.”

Much love,

Anne Maria Clarke

x x x

The myths, legends and archetypes; the artists and their wondrous creations - are the treasures, each reflecting as aspect of the mystery, that maybe strung upon Ariadne's golden thread like translucent pearls upon a priceless necklace.

It seems that those artists, thinkers and even their patrons like the Medici, throughout the many centuries of this story – have somehow resonated with this quest. They have championed the theme of divine love and beauty and have attempted in their various ways to express – to re -imagine for us – what this illusive mystery may be or may not be.

The high renaissance artist Raphael once said of the archetype of the goddess, Venus and the Madonna alike...and this seems like as good as any place to end...

“She is divine serenity made human flesh.”

Much love,

Anne Maria Clarke

x x x